limitations permitted

Custom stereoscopic film viewer (high impact polystyrene, resin, aluminium, glass, steel, rubber, electronics)

23 x 29 x 12 cm (2009)

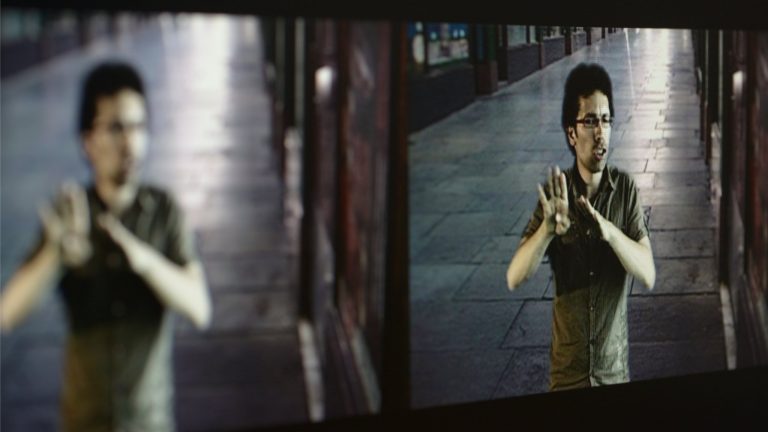

Handheld personal viewer as part of Manu Luksch’s Limitations Permitted work that interrogates the hyper-regulation of public space. A series of short silent stereoscopic videos quote extracts from specific local UK byelaws and laws that affect public space, interpreted into British Sign Language (BSL). BSL encodes meaning in three dimensions of space and one of time; stereoscopic video allows full expression of the language.

Commissioned by Peckham Space.

THE VIEWER

The videos are presented for individual viewing in a hand-held viewer, which is designed to run on batteries for 8 hours. Off-the-shelf 3D head-mounted displays were either too low in resolution or too expensive. Engineering a custom solution with miniature LCD screens and a file player would have been ideal, but we needed a working prototype very quickly, so we decided to modify a pre-existing portable video playback device, mounting it behind a pair of eyepieces. Binocular eyepieces present a magnified image to each eye at a comfortable viewing distance, rather like a ViewMaster. The left and right images can be presented independently to each eye (on two screens, or side-by-side on a larger screen), or can be encoded as a single image on one screen. We initially considered using a pair of devices with small VGA (640 x 480) displays, but managing the synchronised playback of the files under their closed operating system was not an inviting task. We were left with the single-screen option, but sourcing a device that had a high resolution screen of the required size and long battery life was difficult. Eventually we found a PMP (personal media player) with a 4.3″ 800 x 480 LCD display, with a fine-enough pixel-pitch to present a smooth and sharp image through the pair of eyepieces. With an auxiliary battery, continuous playback time exceeding 8 hours was possible.

In the viewer, the 3D information could only be encoded into a single image using the anaglyph technique (using red and cyan filters) – most LCD screens do not refresh quickly enough to work with shutterglasses and other polarisation-based techniques. However, even with high-quality filters, there was considerable ghosting and smearing of the image. The remaining option was to place scaled-down left and right images next to each other on the screen, and separating the left and right optical paths with an opaque barrier. This gave each eye a lower-resolution image, 400 pixels wide, but in full colour and with no interference between the left and right eyes.

RECORDING IN 3D

For encoding the 3D information, we initially considered using a prismatic camcorder attachment that allows left and right eye-views to be recorded to alternate fields of interlaced video. Only one camera is required, though the vertical resolution of the image is halved, and there are also limitations on the recording format (MPEG-2 based formats such as HDV do not work). The other option was to use a pair of camcorders mounted about eyes-width apart, running in synchrony. Research suggested that an (expensive) external device would be needed to keep the cameras in sync, or at least to indicate when they drifted out of sync. However, results of an experiment with a pair of (unmatched) miniDV camcorders, started together manually, looked promising when viewed in the prototype viewer. It became clear that the critical factor was not sub-frame synchrony between the cameras, but lens alignment and matching of perspectives. When a neighbour donated an old camcorder to us, we had access to two camcorders with identical lenses (Sony PD-100 and TRV-900). These were mounted parallel and as close as possible on a bar, levelled with a spirit level, with the lenses zoomed to the wide stop. (The camcorders’ width meant that the lens separation was a little greater than average human eye separation, which exaggerated the stereoscopic effect slightly.) Both camcorder transports could be controlled with a single remote control – giving us an inexpensive but very effective standard-definition 3D shooting rig.

ABOUT THE WORK

How do we respond, psychologically and behaviourally, to different public and private spaces? Spaces carry particular histories and are inscribed by rules, both overt and tacit. How secure do we feel given our imperfect knowledge of such rules? Libraries, playgrounds and shopping malls appear to be benign zones, but they are also spaces under observation that generate information about the people who inhabit them, through CCTV cameras, library card readers and ATMs. How willing are we to give up our personal information – in exchange for what?

Multiple layers of legislation hyper-regulate today’s open spaces. Some of these laws are outdated (no sheep grazing in the park), some bizarre (hot air balloon take-offs permitted only in case of emergency), some overzealous (police to disperse groups of two or more persons in public places), some simply unbelievable (no tourist snapshots of bobbies allowed). “Instead of making sure we conform to the way space is regulated, Limitations Permitted encourages discussion about how that happens.”

Peter Bradwell (Demos), ‘Think Piece on Peckham Space’ in Peckham Space. July 2009

Laws and byelaws that hold in a space are typically expressed in opaque language on discreet signs – easily misunderstood, and easily overlooked, if they are displayed at all. Limitations Permitted interprets and presents to the public the specific laws that hold in the public space of Peckham Square. In particular, it highlights the limitations to the Human Rights Act permitted to local authorities through claims of special circumstances. Many of the laws and byelaws that apply to public space existed prior to the incorporation of the EU Convention on Human Rights into the UK Human Rights Act 1998, and have yet to be challenged in light of legal and social change. But compliance with the 1998 Act is insufficient as a guarantor of liberties – the project title is taken from the numerous accessory clauses to the Act that allow exemptions.

While Limitations Permitted reveals laws that hold in the space, it too uses a specialized language to do so – BSL (British Sign Language). Trading the opacity of legalese for the transparency of gesture, it addresses first and foremost a community whose language was long suppressed. In 1880, at an international conference in Milan it was ruled that oral (spoken) education was better for deaf people than manual (signed) education, and a resolution was passed to ban sign language. Generations of deaf people were disadvantaged as a result. Today BSL has come to be regarded as a language of resistance, liberation, and autonomy –one which, in particular, refuses the normalising view of deafness as something to be ‘cured’. However, sign language continues to have a different legal status from spoken language – for example, in the UK, while CCTV is ubiquitous, audio surveillance is prohibited – but conversations in sign language enjoy no such protection from ‘visual eavesdropping’.

Mukul Patel, 7th June 2009