love, piracy, and the office of religious weblog expansion

Participatory, process-based work; installation; edition of 1,500 uniquely hand-censored artists books; website

(2009–)

Love, Piracy, and the Office of Religious Weblog Expansion is a performance and installation constructed around the censorship and distribution of a book. The work continues online as a collaborative reading project.

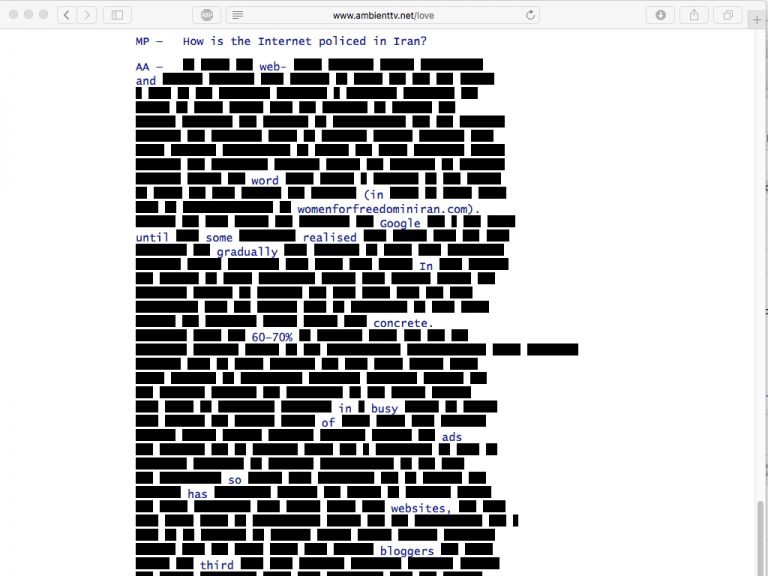

On a censor’s desk lie stacks of identical books awaiting redaction, a file containing proscribed words, black marker pens, rubber stamps, ink pads, and assorted paraphernalia. In each book, a particularly provocative text is censored by hand before being deemed suitable for public scrutiny. The text, entitled Love, Piracy, and the Office of Religious Weblog Expansion, is the transcript of an interview with Iranian philosopher Ali Alizadeh. The censorship scheme is draconian – of the philosopher’s 1,500 word-long responses, only one word is left legible, and it is a different one that survives in each copy of the edition of 1,500. Process mirrors content: Alizadeh traces the history of censorship in Iran from the ’79 Revolution to the age of Google, highlighting the polyvalent impact of new technologies on freedom of expression. His is a chronicle of irony and absurdity – of preemptive censorship by librarians and of piracy by the state, of aesthetic crises precipitated by easing restraints, of the embracing of the web by political hardliners and reformers alike, and of language escaping the control of religious authorities only to be constrained by market forces.

Love, Piracy… continues online as an experiment in collective reading and responsibility. The censored interview is reproduced on the project website. Holders of the book are invited to collude in undermining the censor’s efforts by sharing the unique word of text left visible in each copy. Once a word has been correctly submitted to the website, it is permanently revealed online. The entire text will be rendered visible only if holders of each of the 1,500 books share their words online.

A third modality of the work emerges through the interviews conducted with volunteer censors. Whether installed in a gallery or deployed in a teaching context, the performance aspect of the project involves the work of several human censors who have signed non-disclosure agreements with the artists regarding the contents of the text. For some potential participants, the very act of signing a non-disclosure agreement is a provocation too far – never mind the violence they are being asked to carry out towards the text – and they refuse the encounter. Others happily obliterate words as instructed. Typical interview responses revealed very different and sometimes surprising attitudes towards the politics of information in Hong Kong, the UK, and India.

Concept & Realisation: Manu Luksch & Mukul Patel

Text based on a conversation between Ali Alizadeh and Mukul Patel

Programming – Elke Michlmayr

Soundscape – Stuart Bowditch and Mukul Patel

Supported by – Arts Council England, BMUKK Austria

_____

Love, Piracy, and the Office of Religious Weblog Expansion is one article in the 400-page publication Ambient Information Systems, edited by Manu Luksch and Mukul Patel, London 2006.

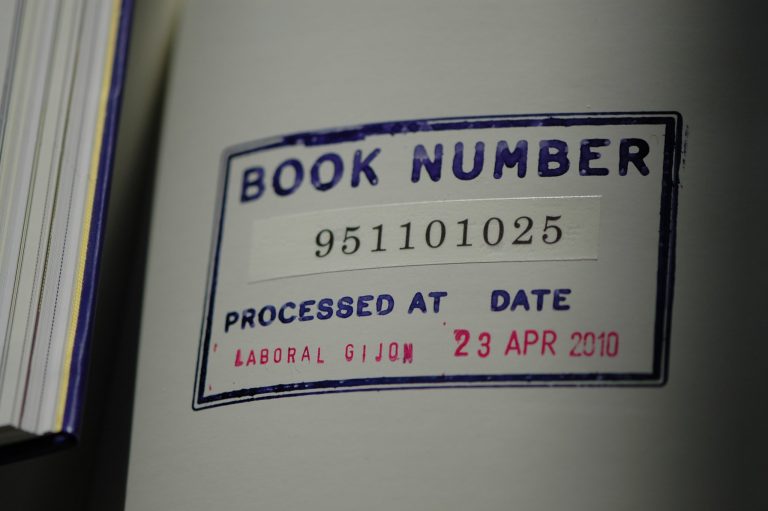

Edition: 1,500 unique & numbered, of which 25 wrapped in stainless steel

ISBN: 978-0-9556245-0-6

available at LondonArtWords on Amazon and online at academia.edu

Ambient Information Systems collects documents and writings from a decade of interdisciplinary arts practice by Manu Luksch, Mukul Patel and collaborators. Interrogating the social and political transformations of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, this practice recalls aspects of the 1910s-20s avant-garde and 1960s-70s conceptual and systems art.

A major essay by media theorist Armin Medosch situates the work of the London-based artists amidst the rise of the ‘creative industries’ idea, inner-city regeneration, and the dot-com boom. Medosch identifies the work as a front in the wave of critical art that has emerged alongside the rise of digital networks and ‘open source culture’, and offers an analysis that draws on systems theory.

Other contributors to the book include independent media activist Keiko Sei on the ‘camcorder revolution’ in Burma; policy consultant and writer Naseem Khan on grass-roots regeneration in East London; activist-artist Siraj Izhar on praxis as process; and philosopher-dramaturge Fahim Amir on techno-democracy.